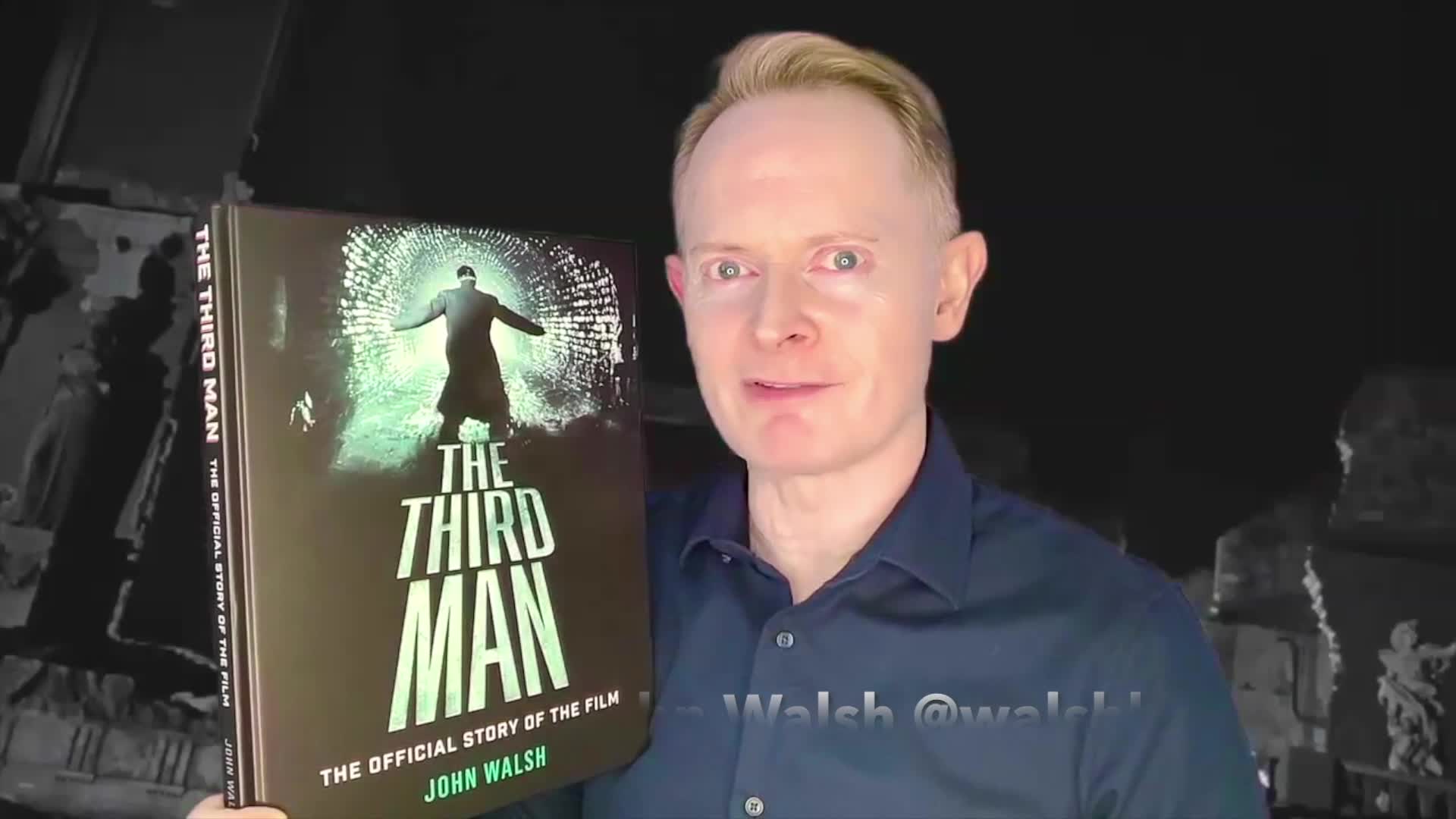

John Walsh is a filmmaker and writer who has written several “official story” books on a variety of films including Dr Who and the Daleks, The Wicker Man and Conan the Barbarian. He latest book details the official story of The Third Man, once declared the greatest British film ever made. I recently spoke to John about the film and his new book (which can be bought here and all good bookstores).

The first question I’d like to ask is what made you want to write a book about The Third Man to begin with?

With the 75th anniversary approaching, it was an excellent opportunity to create a large-format coffee table book that shows some classic film noir images in a new light. The longevity of the film and the behind-the-scenes story have fascinated me since I first saw The Third Man at film school.

There was a great deal of research that had been published about the making of the film, from books, articles, essays, interviews, documentaries and commentary tracks. It was my job to line up the information and, where possible, straighten any contradictions and include new interviews with the film’s last surviving crew member, script supervisor Angela Allen. The film has received a marvellous restoration from rights holder StudioCanal.

To what degree do you think that the film is a direct reaction to the uncertainty and fear engendered in Europe in the aftermath of war and the uncertainty over America and Britain’s relationship to Soviet Russia?

The film does make the most of the political tension of the post-war chaos and divided loyalties of some countries. Still, the reality was that British Hungarian producer Sir Alexander Korda had money in Europe he needed to spend, and dispatching Graham Greene off to create a story for a film was the primary motivating factor.

Greene wrote the novella in preparation for writing the screenplay, do you think that may have impacted the way that he approached the screenplay?

Yes, the novella was also a prelude to the screenplay that was being planned. Greene liked to organise his thoughts when writing fiction in a way that The Third Man lent itself to a novella. It allowed Greene to construct his narrative and make it work on the page before the sometimes cumbersome task of translating to a screenplay where the dialogue and occasionally sterile narrative direction can strip the drama of its emotional heart on the page.

How crucial do you think Carol Reed’s choice of Anton Karas was to giving the film its unique sound and how important do you think Karas’ soundtrack was to making the film a success?

The questions about the musical score have followed the film for years. For this book, I asked leading dramatist, composer and author Neil Brand to take a deep dive into the world of The Third Man’s score to give both a historical context for the music and also a contemporary view some 75th years later. This was unusual for the time as director Carol Reed was more comfortable in orchestral arrangements. The music here has become intrinsically linked to the film’s iconic status and was an international recording success, as was the restaurant musician Anton Karas, who was plucked from obscurity to become a worldwide sensation.

The casting process for the film seems to have involved somewhat of a tug of war between Selznick and Reed and Greene with the former wanting Robert Mitchum cast as Harry Lime rather than Orson Welles; how different do you think the film would have been had Selznick got his way?

Selznick was a Hollywood titan, so when he talked, people listened. He was unhappy with the film’s casting and wanted to change the title to Night in Vienna and give the film a boy-meets-girl ending. When he got hold of the film, he changed it, including the opening for American audiences. I cover all of this in the book. Alongside Mitchum, Cary Grant was also offered a leading part. Selznick didn’t like Orson Welles and was adamant that he should not be cast. He knew Welles would be difficult to control, and he was right. But can we really imagine anyone else playing Harry Lime? With future AI advancements, perhaps we might see the film again with these roles recast.

Reed had a particularly awkward time directing cats in the film, could you explain how he managed to find a way to direct them?

There were no places to get trained cats or any animals for film and TV in those days, so the crew had to make do with several cats, tins of fish, and the patience of the film crew. Future James Bond director Guy Hamilton was tasked with finding the cats for the shooting at Shepperton Studios and searched high and low to find cats that looked the same, including the one owned by his landlady.

To what extent do you think the character of Anna Schmidt evolved throughout the production?

Initially, Greene had planned for Anna to walk off in silence with Holly Martins. Carol Reed thought it would be a more memorable ending if she left alone, so this was part of the changes that took place during the shoot. Because this was an American co-production, the script also came under the watchful gaze of the US Production Code. There could be no explicit talk of a sexual relationship between Harry Lime and Anna Schmidt.

Reed mentions in a 1972 interview about the film that location filming was uncommon in filmmaking them because of the expense and most films were shot at studios. Do you think The Third Man demonstrated the importance of location filming and therefore encouraged other directors to follow Reed’s lead and shoot on location more?

The Third Man needed to film in Europe to release money Korda had in Austria. There was no way of recreating the scale of the crumbling city of Vienna in the studio, so this was an effective balance. Even now, it is seamless when the film cuts between the filming at Shepperton Studios and the location at work. This is to the credit of a great creative and technical team working behind the camera in particle Director of Photography, Robert Krasker, whose cinematography won him the Oscar. But it is true that it was a breakthrough for so much of the film to be shot on location for a medium-budget film at the time and showed what was possible.

How different do you think the British film industry is today compared to when The Third Man was made?

The Third Man was made at a time when there was a large demand for British feature films, so the home market was thriving. This resulted in a factory-style industry akin to Hollywood’s golden era, with actors, creatives and technical staff on long-running contracts. The partnership between great talents such as Carol Reed and Graham Greene could find security, appreciation and continuity for their work. Today, the market is freelance, and film productions are set up individually, so it is unlikely a film like The Third Man would have been produced under the same circumstances.

What is the one thing you hope people most take away from the book?

With all of my books, I bring an alternative or new perspective on a classic film. The book’s design is crucial. Titan Book’s designer, William Robinson, worked his magic on this book to create a sense of the era with Dutch tilts and restored photography, giving it a contemporary point of view. Many of the photos, artwork and even letters in the book are being published here for the first time. If viewers take a second look at a film or even a first, then my work is done.

With thanks to John Walsh and Titan Books. If you like this interview make sure to buy a copy of the book and if you need any more convincing, do check out my review of it here.

Pingback: The Third Man: The Official Story of The Film Review | The Consulting Detective·