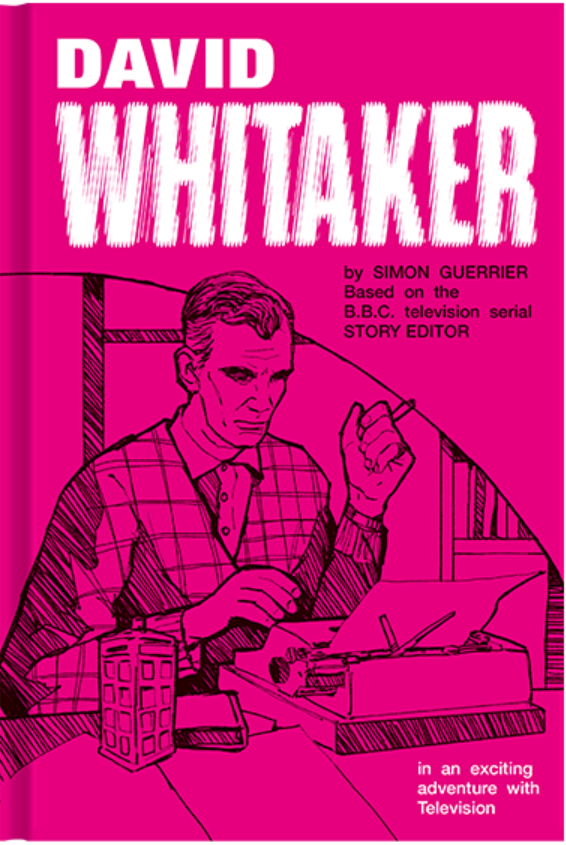

To celebrate Doctor Who’s 60th anniversary, I’ve been conducted a few interview with different writers and actors from across the show’s decades long history. Simon Guerrier is a long time friend of the site and has been interviewed for it several times – this time I spoke to Simon about his great new book on that supremo of Doctor Who – David Whittaker.

Hi Simon, thanks again for agreeing to this interview. The first question might seem to be a bit of an obvious one but what made you want to write a biography of David Whitaker?

Hi Will. My interest was really sparked while researching my Black Archive book on the 1967 Doctor Who story The Evil of the Daleks, published in 2017. The more I looked through old papers and spoke to people involved, the more tantalising Whitaker seemed. He was story editor on the first 53 recorded episodes of Doctor Who (including the unbroadcast pilot and fourth episode of Planet of Giants), and he wrote more episodes of Doctor Who in the 1960s than anyone else. Yet we knew very little about him, or the influences on his work. So I started looking into that, initially thinking it might make a 5,000-word feature for Doctor Who Magazine.

Can you tell us a bit about David Whitaker’s career prior to working on Doctor Who?

His first known work as an actor was in 1950 with the Stock Exchange Dramatic and Operatic Society (Sedos), which suggests he’d been working in the City of London somewhere, perhaps with his father — who was an accountant representing people including Charles Hawtrey, later famous in the Carry On films. Sedos is an amateur dramatics company but David’s work there quickly led to a professional job with the Harry Hanson company, and he was regularly in stage work and getting good reviews over the next five or six years.

In 1956, he began sending ideas and scripts to the BBC, and in June 1957 they broadcast his first TV play, a drama called A Choice of Partners. The following month, David went to meet the head of the BBC’s script department, Donald Wilson, to discuss ideas for further plays and by October he was on staff. His job was to read submitted material and encourage new writers, and get other people’s scripts ready for production and then have them properly filed. But he was also writing — as part of his day job and also in his own time. He wrote for the children’s show Crackerjack, he wrote the links to song-and-dance shows, he wrote lyrics for songs used in TV shows, he wrote serious plays and musicals and a thing about the Congress of Vienna (1814-15) all done as if it were a modern news broadcast — sort of like an early version of Horrible Histories. By 1961 he was script editor of light entertainment, and then in 1962 he became script editor of the prestigious Sunday-Night Play, and while overseeing its rather highbrow output he was also writing for the soap opera Compact. So a really varied career, and a lot of experience of all kinds of TV and what you could achieve in a studio — which I think was just what Doctor Who needed.

Whitaker’s work with the Daleks is one of his most important contributions to Who – both in writing for them in the TV series but also in the TV Century 21 comics and the play The Curse of the Daleks. When writing the book did you get an insight at all into how Whitaker felt about the Daleks? Did he enjoy writing for them do you think, or did he think they were simply the most popular adversary of The Doctor and so just the easiest to use in his work?

In 1978, David wrote to Doctor Who fan Gary Hopkins — who went on to a very successful career as a TV writer himself — and called the Daleks worthy of Jules Verne. So yes, I think he was very proud to have been involved in their creation, though he gave all credit to writer Terry Nation. And yes, I think he must have enjoyed writing for the Daleks and expanding the lore around them. He also did a script polish on the second Dalek movie, and wrote the greater share of the first two Dalek annuals. I wrote a feature for Doctor Who Magazine (issues 558 and 559 in 2020) about how his efforts helped turn the Daleks into a cultural phenomenon.

The Edge of Destruction was Whitaker’s first broadcast script for the series and is an intense and dark story. How did Whitaker approach writing this story? It was written on fairly short notice wasn’t it?

This is one of the things I address in my new Black Archive book on The Edge of Destruction. The claim has often been made that the oddness of the story is down to it having been written very quickly — some sources claim in one day or over a weekend. But I’m not sure that holds up, not least because there were six weeks between it being commissioned and the scripts needing to be in, and there’s also evidence of different stages of rewrites. I think the oddness of the story is more down to what it was required to do, which is what a whole chunk of my book is about.

Whitaker’s historical tale The Crusade is one of those stories that is sadly missing from the archives. Whitaker was fascinated by the Third Crusade and that is clear from the details he put into the story – is Whitaker’s clear passion for the subject matter part of why this story is still one of the most popular pure historical stories the series has produced?

Whitaker was certainly interested in history. He thought the play he wrote about the Congress of Vienna, which I mentioned above, was the best thing he ever wrote and he had ambitions to follow it up with a film about Napoleon, which may have influenced the plot of a Doctor Who story he commissioned, The Reign of Terror (1964). He also had in mind a Doctor Who story about the Spanish Armada, rejected by his successor Gerry Davis in 1966. And a good chunk of The Evil of the Daleks is set in 1866 — the first Doctor Who story to really mash up history with science-fiction, which is now a staple of the programme. Yet he also recognised early on that Doctor Who’s out-and-out science-fiction stories were the ones that really caught on with the public; there’s correspondence in which he admits as much.

The Power of the Daleks is the first story to deal with a post regenerative Doctor – was Whitaker nervous about this challenge? Do you think he was aware of how significant his depiction of a Time Lord after regeneration would be? And given that this was, at the time, effectively a soft reboot of the show, did the make or break nature of the story make him double his efforts to ensure the script was as engaging to audiences as possible?

I’m not sure there’s any sign he was nervous, and we can see from surviving rehearsal scripts that he delivered what he’d been asked for with a slightly austere new Doctor in the mode of Sherlock Holmes — Holmes is cited in surviving paperwork from the time. But the BBC’s head of drama, Sydney Newman, objected to this character, prompted by Patrick Troughton’s own misgivings about such a talkative character meaning he’d had too many lines to learn each week. That meant the story was rewritten at the last minute, pushing recording back by one week. Whitaker wasn’t available to do these rewrites as he was apparently out of the country, so Dennis Spooner was brought in. Spooner later recalled that Whitaker was in Australia but I don’t think that’s right — again, I go into that more in my biography.

The key thing, though, is that Spooner and Troughton made the new incarnation of the Doctor more quirky and odd than Whitaker wrote him — and the general consensus seems to have been that they went too far. Relatively quickly, the performance was reined in, the Doctor’s recorder featured less often and the tall hat disappeared. Producer Innes Lloyd gave a newspaper interview acknowledging that they were going to make the Doctor more serious. And so when David was writing his next story, The Evil of the Daleks, he seems to have been asked to make the Doctor darker, more mysterious and more like Sherlock Holmes — basically, the brief he’d been given on his previous story. So he’d been right all along!

How influential do you think Whitaker was on the stories that he script edited? How much did he change of the scripts submitted to him?

I think he was hugely influential. The tone of that first year of Doctor Who is very consistent, as are the four regular characters — and that’s all down to him. He was constantly reworking scripts, making them more practical by reducing the number of sets, or adding elements to benefit the series as a whole. We can trace his revisions in some of the surviving paperwork, such as the way the Doctor’s brilliant final speech in The Dalek Invasion of Earth was honed by him and then by the actors in rehearsal. But that’s the point — David was part of a team, and he was very keen not to take credit for what the team produced. In his letter to Gary Hopkins, he praises everyone else — actors, producers, writers, directors and designers, and side-steps his own contribution.

Whitaker of course spearheaded the novelisation of Doctor Who stories. How differently did he approach the process of novelisation to writing for the series? Did he have more freedom when adapting his own story, The Crusaders than Nation’s first Dalek story or, given how different the opening of Doctor Who and The Daleks is to the TV story, was he given carte blanche to do what he liked?

From surviving correspondence, it’s clear Whitaker was aware that his novelisations had to work as a record of the stories as broadcast, as there was no other way to revisit episodes after they’d been aired. So where he changes things, there’s usually a good reason. Sometimes its structural — a novel suits longer sections whereas TV tends to favour short scenes, while telling the story from Ian’s perspective also affects some of his choices. But there are also practical things, for example in his Dalek novel he had to introduce the four regulars in a different way from the TV series because that first serial was the copyright of Anthony Coburn. In fact, Whitaker seems to have taken elements from the earliest outline for Doctor Who, where an accident prompts people to rush into a police box that turns out to be a spaceship, and also used elements from his own childhood.

When Whitaker sadly died of cancer in 1980, his novelisations of The Enemy of the World and Evil of the Daleks were left incomplete. How far did he get with the novelisations? Do you have any indication as to how faithful or otherwise they would have been to his original scripts and how similar or different they were to the eventual novelisations?

David submitted a synopsis for how he’d novelise The Enemy of the World in October 1979, which was filed away by the publisher and ultimately printed in Doctor Who Magazine #200 in 1993. No contract for him to novelise the story is known to survive, but one does survive for The Evil of the Daleks, dated December 1979 and my guess is that he was contracted for both at the same time. A single page survives of his novelisation of The Enemy of the World – I tweeted it https://twitter.com/0tralala/status/1658212312157659142. It doesn’t look as if this was passed on to Ian Marter when he took over the novelisation after David’s death in February 1980. David’s synopsis is intriguing, though. It shows David grappling with the fundamental challenge that the TV serial was based on a visual gag — the Doctor and baddie Salamander are played by the same actor — and obviously the novel wasn’t restricted by the practicalities of showing them both on the screen at the same time.

Enemy of the World has strong messages about populist politicians manipulating the populace and how people can be tricked into an entirely fake reality – how much do you think this has contributed to the story being, particularly since its recovery, viewed as one of Troughton’s best stories?

Yet, it feels quite prescient for a story set in 2018, doesn’t it? I’m not sure how much that explains the appeal of the story. To be honest, I didn’t think there was much to The Enemy of the World when only Episode 3 existed (for all I love Griffin the chef), but the recovery of the other episodes demonstrated the scale and ambition of the story. Its peppered with comedy and visual interest — such as the woman with the pram — that you don’t get from reading the script or listening to the soundtrack. But that means those are things which David didn’t contribute! But also, director Barry Letts claimed to have changed several things from David’s drafts – and I go into some detail on what we can deduce about David’s version.

Whitaker’s last story was The Ambassadors of Death. Given that there was an intense number of rewrites on this story, despite only Whitaker’s name appearing in the credits, do you think the rewrites contributed to Whitaker not producing another script for the series?

David delivered scripts for three of the seven episodes and was then paid off, and even the episodes he wrote were largely reworked by other people. Barry Letts, who was by then producer of Doctor Who, says on the DVD of The Enemy of the World that he didn’t think much of the scripts of that story and that David was “Who’d out” after so long working on the series, which suggests Letts would have been in little hurry to employ him again. But script editor Terrance Dicks sent David a friendly letter after The Ambassadors of Death was broadcast saying how much its success was down to him, and Terrance told me he really respected David and was embarrassed by the whole business with Ambassadors. So maybe, if David hadn’t moved to Australia in February 1971, Terrance would have offered him something else.

As someone who has written Doctor Who stories yourself, did you feel that you were at all comparing how you wrote Doctor Who to Whitaker? Could you see any particular similarities in your approach or do you think you both wrote Doctor Who and approached the writing of it quite differently?

A lot of the practical challenges haven’t really changed — trying to tell big, imaginative and exciting stories with a limited number of actors, where the big ideas have mostly to be realised in what characters say. I also recognise many of the frustrations David faced, and admire how hard working he was, and how hard he worked to encourage and support other writers. He was a very generous, courteous and conscientious writer, and that’s meant he’s been very enjoyable company over the past few years I’ve been working on this book.

What do you think Whitaker’s ultimate legacy will be?

We’re his legacy, Will. He encouraged active participation in Doctor Who — and in writing more generally. The books, comics and other media he worked on do the same thing as the strong cliffhangers he was so keen on for the TV series, and the references in TV episodes to unseen adventures. It’s all about opening up the series to our imaginations and letting us in. Oh, and without him there would have been no Daleks — that’s probably quite a big thing as well.

Thanks again for agreeing to this interview Simon. Finally, what other projects are you working on at the moment?

Well, these two books are keeping me very busy but I’ve also co-written The Daily Doctor and Whotopia for BBC Books, and have some things in the pipeline for Big Finish. There are some other bits and pieces going on but all in early stages.

You can buy a copy of Simon’s excellent biography of David Whitaker here